The New York Times

By JOSHUA YAFFA

Published: December 9, 2007

JUST before midnight on Nov. 3, a white truck pulled up to the Frank Viola Homing Pigeon Club, on a dark and quiet stretch of Stillwell Avenue in Coney Island. The air was cold and smelled faintly of the sea. Two men hopped out of the truck. One opened its rear doors. The other approached a handful of older men who were standing in the street. “How many you got tonight?” the man asked.

Fourteen crates, came the reply. The crates, which were stacked near the curb, held hundreds of pigeons.

It was race night at the Viola club, and for a few hours, the club’s pigeon fliers had been tagging the birds’ feet with electronic bracelets and scanning the information on the bracelets into a master clock in preparation for their 300-mile overnight journey to the town of Somerset in southwestern Pennsylvania. There, half an hour after sunrise, at a truck stop just off Interstate 76, the birds would be released to race back to Brooklyn, with the earliest arriving back in early afternoon.

Homing pigeons may be icons of the city, with rooftop bird coops a familiar image like the skyline, but the sport has been in decline for the last half century. Although only a couple of hundred pigeon fliers remain in New York, however, that small band, organized into a half-dozen or so clubs like the Viola, forges on, participating in races that span hundreds of miles and conducting hundreds of races each year.

The races are divided into two formal seasons — one in the fall and one in the spring — with prizes awarded both for weekly races and season-long performance.

The Somerset race was the last of the fall season for the Viola club, and a crucial one for John Fasano, a 75-year-old retired roofer who began racing pigeons in New York when he was in his teens. Before the start of this race, Mr. Fasano led the club’s rankings for the season’s best overall average speed, an award that is the closest thing the sport has to an annual championship.

Mr. Fasano was feeling optimistic when he checked in his birds at the Viola club earlier that night.

“I wish I could fly this good every year,” he said. “I’d like to finish with a bang.”

As the drivers loaded their cargo into the back of the truck outside the clubhouse, the soft chatter of the birds could be heard through the wooden slats in the crates. The fliers said their goodbyes. “Guys, I’ll see you tomorrow,” David Kurtz, wearing a heavy flannel coat and a black baseball cap, said to his birds. Then the truck let out a low rumble and disappeared into the darkness.

•

New York’s pigeon clubs, loosely organized by geography and custom, are a cross between an urban sportsman’s lodge and a time capsule of immigrant, working-class New York. Even as recently as a generation back, fleets of racing pigeons swirled above New York like pulsing gray clouds, but the numbers of racers and birds have thinned, with not enough new fliers to replace the old.

Yet the dynamics of a pigeon race have remained mostly the same. The birds are trucked to a central “liberation point” anywhere from 100 to 500 miles from the city, where they are released so they can fly home. The birds’ owners sit waiting by the coops on their rooftops, or in their backyards. Most birds return within several hours, but some take days or even months. Others never come back.

Homing pigeons start their training a few weeks after birth, which, for birds that will compete in the fall season, means sometime in early spring. After the young chicks learn their way around the coop, racers start taking the birds on training flights, first carrying a crate of young pigeons down the block, then driving them to New Jersey or Pennsylvania and releasing them so they can fly home.

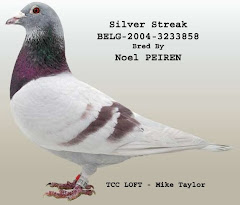

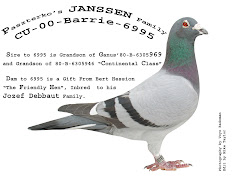

Longtime fliers say they can spot a winner by looking at a bird’s eyes, its plume, the white of its beak. Homing pigeons are members of the same family as common street pigeons, Columbia livia, but the two classes of birds have little else in common.

“It’s like comparing a Lamborghini to an old pickup truck,” said David Martinez, a New York police detective who is a member of the Viola club.

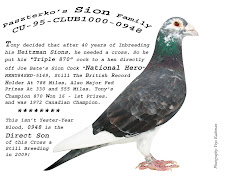

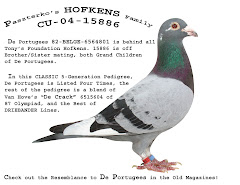

Pigeon fliers, whose flocks usually number 40 to 80 birds, do indeed treat the birds like fine automobiles, feeding them a careful tonic of antibiotics and vitamins, and birdseed blends with names like Tipple Mix and Vinny’s Candy. Steroids are forbidden, and there is random drug testing at many larger races. A champion pigeon can fetch several thousand dollars at auction, with the hope that it will breed future generations of winners.

“It’s like having your own sports team,” said one Viola club flier. “And you’re the owner, the trainer, the doctor.”

In the early 20th century, matters were a bit less elaborate. The city’s pigeon fliers raced by paying a railroad conductor a couple of dollars to let the birds out when a train bound for Pennsylvania reached Erie. In those days, training meant riding the Staten Island Ferry for a nickel and releasing the birds on the other side. The only supplement a racer might use was a rusty nail placed in the birds’ water dish, to give his pigeons an extra boost of iron.

•

If there were a commissioner for pigeon racing in the five boroughs of New York, in recent years that title would have gone to Frank Viola. Mr. Viola, a slight, white-haired man from Bath Beach, Brooklyn, founded his namesake club in the early 1990s and ran the Frank Viola Invitational for the last 16 years. With 1,500 birds, the race became one of the largest in the city, the Kentucky Derby of the pigeon season. This year, the Viola Invitational was scheduled for the first Saturday in October.

However, two nights before the race, when the city’s pigeon men would ordinarily have been readying their birds for the trip to the starting point in Cadiz, Ohio, they were gathered at Torregrossa and Sons funeral home in Bensonhurst. Mr. Viola had died the previous day at age 87, and the pigeon men had come to pay their respects.

A group of fliers stood in the hallway at the wake, telling their best Frank Viola stories. Remember how his birds flew missions for the Army Signal Corps in World War II? And how about the time he turned down $20,000 from a Taiwanese breeder for one of his champion pigeons?

Mr. Viola’s nephew Peter, who in recent years has taken on a larger role in running both the club and the race, decided to cancel the Viola Invitational in light of his uncle’s death. “He held everything together,” Bobby Presto, a retired New York police officer and pigeon flier, said of Mr. Viola. “He was like the godfather.”

•

It was a cold fall afternoon, a week after Mr. Viola’s funeral. The sun was starting to dip behind the Coney Island parachute jump, and a 44-year-old flier named John Mantagas was waiting for his birds to return. Mr. Mantagas had entered 10 pigeons in a contest called the Main Event that is sponsored by a club in the Westchester Square neighborhood in the Bronx. The birds, 600 in all, were flying back that day from Weston, a small town in West Virginia.

Mr. Mantagas was sitting on the roof of his two-story house in Coney Island, the ground floor of which he rents to the Viola club. Of the 10 pigeons he entered — most fliers enter 5 to 20 birds in a race — he was favoring a blue bar hen wearing the band number 511.

That bird, he said, had been “sitting on eggs,” a strategy that involves putting a handful of fake plastic eggs in the nest of a female pigeon in the days before a race. If a bird thinks it has been separated from its unborn chicks, the theory goes, it will fly back faster to the coop.

Nevertheless, no one is exactly sure what gift of biology allows pigeons to navigate their way home from a far-off, unfamiliar place. In studies in the 1960s and ’70s, scientists at Cornell University said that pigeons use the earth’s magnetic fields as a guide. Other research has pointed to the birds’ heightened sensitivity to low-frequency sounds. A group of Italian researchers suggested that the birds navigate by smell; in Italy, birds travel south toward olive groves, or north toward garlic fields.

In Brooklyn, meanwhile, the sky grew darker, the air cooler. “All I want is one,” Mr. Mantagas said. “Just give me one bird.” By around 4 p.m., his cellphone started ringing. Staten Island, the Bronx, Queens — they all had birds. Vieni Benedetto, a flier who lives in Bay Ridge, called to say he got one, too.

“Benny, you got a good one!” Mr. Mantagas said.

“You might be buying us all dinner,” he added with a deep, raspy laugh. “We want linguine with clam sauce and fried calamari!”

He shut the phone and went back to staring at the sky. As a seagull streaked past, Mr. Mantagas started talking about family. “My kids love the birds,” he said of his children, ages 2, 3 and 11. “But I don’t know if the sport will be around when they’re older.”

These days it can cost several thousand dollars a year to raise and train racing pigeons. Not to mention, Mr. Mantagas said, all the other distractions of modern life with which pigeon racing must compete.

A minute later, a dark gray bird started a sharp dive toward the roof.

“Thank God!” Mr. Mantagas said, popping out of his chair.

“That’s her!”

His hen was home. Inside the coop, she drank greedily from a water dish. Although the bird had returned too late to place among the top winners, Mr. Mantagas was happy. “You made it,” he said, picking up the bird and giving it a soft peck on the top of its head. “And here I was, thinking you’d never come home.”

•

A little after noon on Nov. 4, just 12 or so hours after the white truck had left the Viola club and headed for Pennsylvania, Mr. Fasano — the flier who had a good chance to snare top honors for overall average speed — was pacing on the roof of his house on Avenue Z in Gravesend. Mr. Fasano was waiting for his birds to return. This season would be his last, he had decided, and he wanted to go out a winner.

Soon his favorite bird, a blue-checkered cock, appeared on the horizon, its wings pumping. Mr. Fasano reached into a crate at his feet to grab a chico, a bright white, non-racing bird that fliers use like a flare to attract the attention of incoming pigeons, and threw it into the air. Noticing the chico, the cock flew toward the roof and landed on the edge of the coop, a few feet from the electronic timer that would record its return.

Mr. Fasano took a few gingerly steps toward the bird, shaking a plastic tub of birdseed. “That’s a baby, go inside,” he said softly. The timer beeped, registering the bird’s arrival. 13:02:11. A little more than five hours from Somerset. It was a good time, maybe a winning one. After a few more birds returned, Mr. Fasano jumped into his car and set off for the Viola club, a few exits down the Belt Parkway.

•

The Viola club’s quarters are about the size of a studio apartment. One wall is lined with pigeon crates; on another is a faded-green chalkboard for posting race results. Mr. Fasano and the other fliers had gathered at the club to hand over their clocks to Peter Viola, who was entering the times in a computer. “Going out a winner,” Mr. Fasano muttered to himself. “That’d be something to talk about all my life.”

Although the club was full of loud talk and pigeon stories, the mood, in the absence of Frank Viola, was different. The place felt totally empty, his nephew said.

In recent years, as his uncle’s health declined, Peter Viola helped him train his birds, and the two men would drive 70 miles into New Jersey for practice flights. “We’d load the birds early in the morning,” Mr. Viola said, “stop at a bagel joint off Route 22, get some bagels and coffee, go sit up by the lake, release a few birds at a time, just sit and talk.”

After Peter had entered all the times, the results were posted. Mr. Fasano had come in second for the day’s race, beaten by a few yards by another Viola club flier. But his finish was strong enough that Mr. Fasano would earn the trophy for the year’s best overall average speed.

“Congratulations,” Mr. Viola said to him. “You did it!”

Mr. Fasano shook hands all around. Winning would get him a plaque, maybe a short article in The Racing Pigeon Digest. The Viola club used to hold an end-of-the-season awards party, but the event was canceled a few years ago. “These guys are interested in pigeons,” Peter Viola explained. “They ain’t interested in dancing.”

By 5 p.m., the men had filtered out onto the street. A few climbed into their cars to drive off; others came up to Mr. Fasano to offer their congratulations. The Viola club would miss him, they said.

“Oh, I’ll still be in the coop every day,” Mr. Fasano said as he lingered for a moment by the club’s open door. “I can’t stay away from the birds.”

Read more ...